This is a selection of things that I find myself discussing with teachers regularly. We all crave simplicity, but actually, when teaching is great, there’s a lot going on. It’s unavoidable- but we can still try to break it down. As with any generic post it might appear to ignore subject-specific curriculum matters but importantly, each of these things has a subject/curriculum home – they don’t make too much sense outside of talking about teaching specific things to specific students. Also – it’s not ‘THE NINE KEY THREADS’… it’s ‘some key ideas in what appears to be a list of nine at this point’ – before you tell me what I forgot or someone says ‘relationships’. I know; that’s all in the mix. It’s just that I almost never see lessons where that’s a major problem. Feel free to add yours below.

Here’s 9 key ideas for maximising learning.

Expectations: If you don’t ask you don’t get.

Nobody would think they have low expectations of students but I regularly observe that some teachers have much higher expectations than others. They create a more intense sense of purpose; they’re that bit more bothered about standards of behaviour, talk, writing; they insist on accuracy and detail and don’t accept mediocrity; they’re more demanding of students in terms of their effort and general work load. They drive lessons with an energy that says ‘you can achieve, you can succeed; you can improve; you can do better.’ There’s a sense of belief.

Aim for a stronger core; not more extras.

If you make a list of the key elements of your pedagogical repertoire – eg your favourite TLAC strategies or the six elements of Making Every Lesson Count or Rosenshine’s Principles or our Walkthrus, there’s already plenty to work on right there without adding bells and whistles. If you want all students to learn more successfully, including those at the margins, there is probably more mileage in just doing these core things better – questioning, explaining, modelling, scaffolding, retrieval practice. Adding extra lessons and interventions might be a poor use of time compared to preparing your core lessons more thoroughly.

Build self-esteem from accomplishments.

At a time when there’s a lot of talk about post-lockdown recovery, it’s important to emphasise the role of successful learning in building students’ confidence and general well-being. Ron Berger, for example, talks of the importance of building students’ esteem through accomplishments, supporting them to achieve excellence – including some modelling and redrafting Austin’s Butterfly style. The ‘strategy v comfort’ study reported here highlights how students can feel more supported when they are enabled to learn more – rather than simply being given care and comfort. And Peps McCrae describes the role of success as a driver for motivation in his superb book, Motivated Teaching. This all adds up to the need to construct learning sequences such that all students feel successful- building steadily on what they can already do, using what they already know, not letting them flounder or feel out of their depth.

Ambitious goals; achieveable steps.

An important balancing act with curriculum sequencing and the messages we give students is to raise their sights high, whilst making ambitious goals seem achieveable. The long-term goals need to be challenging – perhaps audaciously so! But then the path to success needs to feel like a series of manageable steps. Designing those steps is a key element of curriculum thinking. The analogy I often use is from mountain climbing: we’re all aiming to reach the top of the mighty mountain… but first, let’s get to that first ridge, just there. It’s important to create a high success-rate through the nominal size of these steps. If students are struggling… make the steps smaller. If they’re flying, make them bigger.

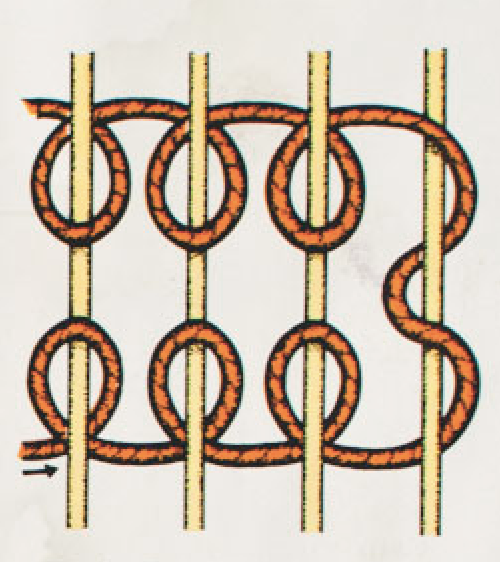

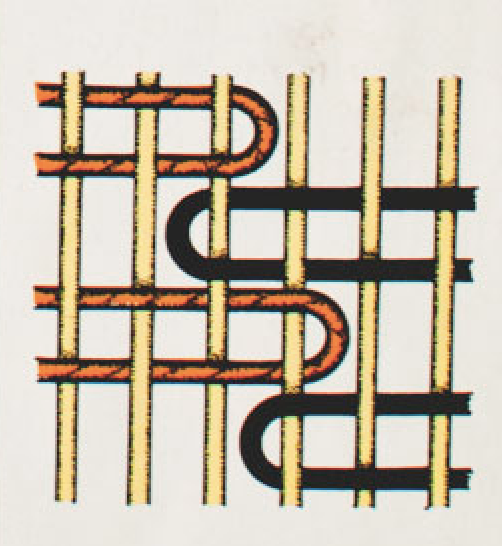

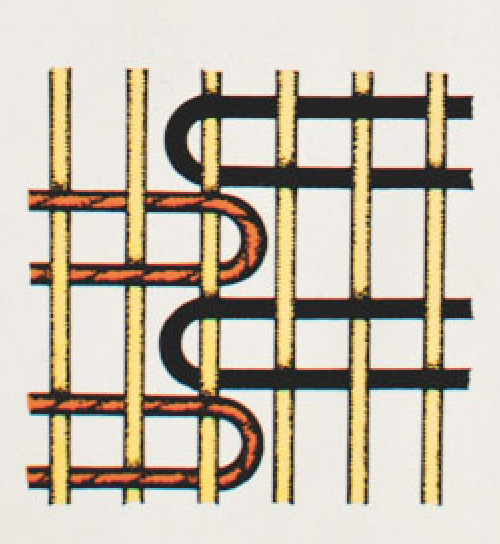

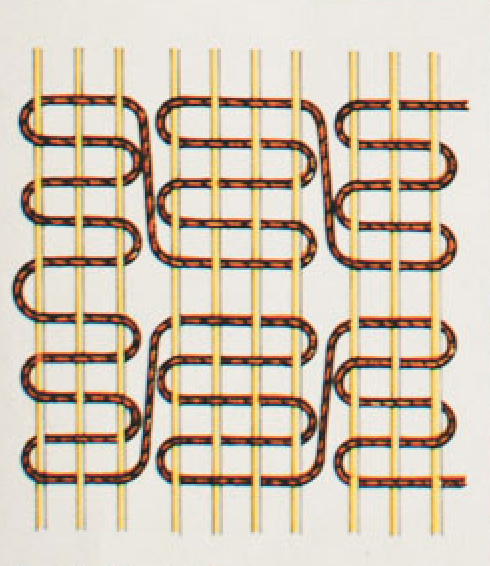

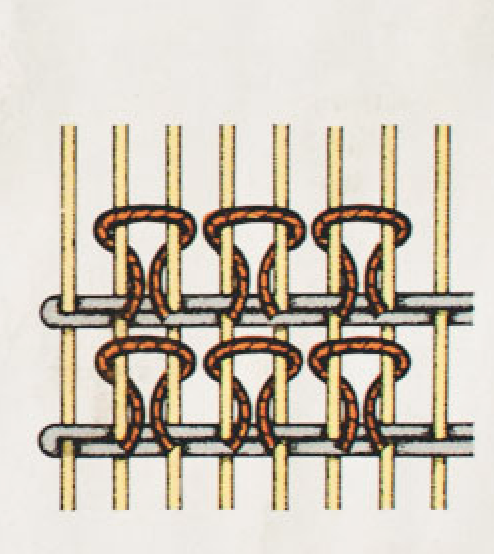

Weaving a fabric of knowledge goals.

If you think in terms of schema-building, students’ understanding and competence will develop over time as they knit together a) experiences and observations b) themes, narratives and broad ideas -their general sense of the study domain – and c) specific facts and knowledge elements. This means we have to attend to all three elements in our teaching:

- building understanding on concrete foundations, starting with students’ prior knowledge and experience.

- using narratives that guide students through the material, linking it all up,

- ensuring students gain the experiences and access the visual supports needed to help make sense of the material in hand.

- allowing time for students to explore their own understanding, self-explaining, rehearsing, self-testing and checking.

- ensuring retrieval practice is varied, based on material that’s been thoroughly explored already. mixing specific skills and factual elements with more holistic, synoptic elements.

To use the weaving metaphor, we’re partly making the structure of the overall fabric so it has strength and continuity and we’re partly creating patterns from specific details of colour and texture that make it interesting, joyful, beautiful. We can’t do one without the other. It means that we need an eye on the overall conceptual framework in the material we teach, and perhaps obsess less on students knowing every little detail.

Engaging everyone, not just a few.

I’ve explored this theme many many times – eg here and here. It’s so important for teachers to avoid the assumption that students are learning merely by being present in the room, following what others are doing and saying and writing stuff down. They need to be in there with you, part of it all, thinking, ready to contribute, processing their ideas, checking their understanding. This means:

- engineer attention, don’t hope for it. Give students tasks to do that make them connect new ideas to existing ones or simply practise what they’ve already been taught. All in.

- create ongoing accountability for thinking and participating through cold calling; make it the norm; the default. Do not let the same students dominate your lessons (I see this so often still).

- check for understanding. Take time to hear what students are thinking – sample the room, get into the corners, find out who is with you and what the misconceptions might be. Listen to contrasting expressions of understanding.

- pair share. Get everyone talking – make lessons feels dialogic; discursive. There are many ways to do this and regular use of talk partners will be a key element.

Responsiveness. Be ready to go back as well as forwards.

Heed the sage advice of Dylan Wiliam and Paul Black in Inside the Black Box. Formative assessment has greatest power when it provides real time information that teachers use to adapt their teaching in light of how well students have understood. Responsive teaching is key. It means being on your toes, ready to move back as well as forward. It means being agile, nimble.. ready with extra questions, different ways to explain the same idea and ready to adjust the learning goals. No – you do not need to get to the end of your pre-prepared powerpoint every lesson; not if the students aren’t ready. Plan long and then adjust flexibly, lesson to lesson.

Making the best decision about going on or going back relies on getting a good sample from your checks for understanding or micro-quizzing or ‘show-me boards’. But always be ready to go back. Some people find this harder than it needs to be. It’s not just OK to do it – it’s essential that you do.

Exercises. Repetition, consolidation and practice:

If lesson sequences contain a healthy dose of consolidation and practice exercises, everyone wins. We don’t get really good at anything by continually skimming over the surface. Through repeated engagement in similar problem types, similar writing tasks, similar creative processes, similar uses of language – we build fluency and confidence. This matters most to our most vulnerable students but also benefits students who grasp ideas more readily. You can’t be ‘too fluent’ can you? Varying modes of practice is important for motivation and challenge – there needs to be a ladder of difficulty – but giving students that feeling of getting better bit by bit by over-learning, deepening, rehearsing… is mighty powerful. And much better than having a tenuous grasp of a wider set of knowledge. If in doubt, consolidate just one more time and add even more questions to the exercise.

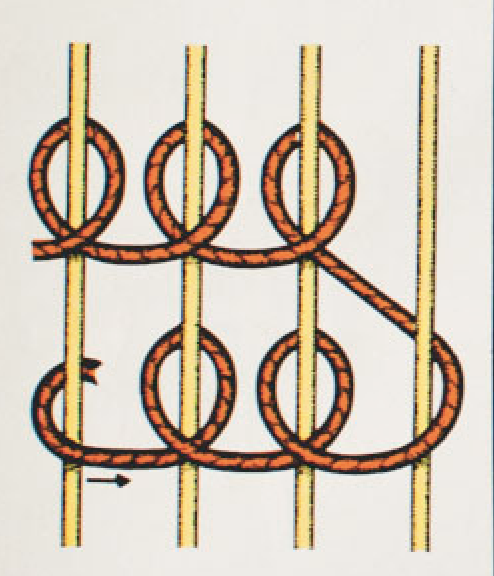

Scaffold high, then bring it down intentionally and gradually.

Personally I feel this is an area with a lot more potential. I still find teachers inhibited by a fear they’re ‘spoon feeding’ so they let students wallow in the limits of their mediocrity – because at least they’re doing it independently.

However, scaffolding is a brilliant concept: let me show you exactly how to do this, now let’s do it together.. now, let me give you some prompts and supports to do it yourself.. now try it totally on your own.

The key is to scaffold high – to show students how to do something that represents real excellence; be ambitious. Then design supports – the prompts and guides that can lead them through. Get them to succeed with the supports – to produce the full-marks answers or excellent creative product. Then, get them to try without the supports. Make this an intentional, explicit moment. Do it brilliantly with help – practise, practise, practise …. now do the very best you can without help. The scaffolding must come down. Turn over those crib-sheets – put them out of reach.

The finished product from all of these elements is something quite wonderful – it’s got that feeling of learning being joyful, confidence-building, uplifting. It’s hard to beat the feeling of learning something really well – of making sense of a big set of ideas or of being able to do something you initially found difficult. Add in the inherent joy and fascination of the subject material that is ever-present in any specific context – and you’ve got the makings of a great learning experience for everyone.

What you’ve got here is the very fabric of good teaching and learning. No fancy embroidery or superfluous bells and whistles (mixing metaphors now, I know) but the very basis of what we should all be aiming for. Thanks for this!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Tom. Pithy & perfect.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This is the most inspiring piece of work I have ever read. I am already planning something to share with our maths department based on the themes from this article.

Thank you very much

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] ‘Weaving it all together: 9 key threads for maximising learning’ by Tom Sherrington […]

LikeLike

This resonated with me (so much so I’ve emailed it to all staff) especially as we’re currently looking at our curriculum and sequences. Easy to read and the weaving references make the concepts clear – something that other documents don’t do as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person